- Home

- Michael Northrop

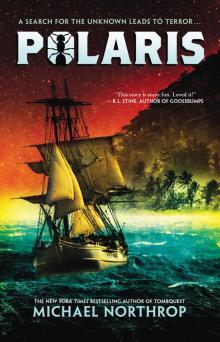

Polaris Page 5

Polaris Read online

Page 5

He took his place on the bow at a large winch known as the windlass, taking hold of its thick rope cable as if preparing for a game of tug-of-war. Being among the lightest, and certainly the weakest, he was jostled into place near the front. Owen took his place on the end. That makes sense, thought Henry. He’s the heaviest and has the most bricks in his head.

At first they hauled in a one, two, THREE! rhythm. They got the slack out of the anchor chain without too much trouble, but after that, things ground to a halt. Despite their best efforts—grunts and groans erupting all along the line—the rope barely moved and the windlass stopped turning. Part of the problem was that Henry—not used to this sort of synchronized activity and not very coordinated—always seemed to be half a beat behind.

Henry rubbed his left shoulder—or port shoulder? he wondered—as they took a break to reassess.

“It’s wedged in good,” said Mario. “Could be caught on a reef.”

“Or some rocks,” offered Manny.

When they went back at it, they used a less elegant method. The three-count was replaced with a simple “Heave! HO!” with everyone falling on their backsides on the second beat. Coordinated or not, Henry could fall on his butt with the best of them.

On the first few tugs, the cable slowly slipped through their hands as they fell to the deck. The rope burn was excruciating.

“AAAH!” hissed Henry, peeling his hands free and shaking them. He looked down at his palms, which had already turned a vicious shade of scarlet.

But a moment later everyone was up again, and Henry scrambled up after them.

“Heave!” called Owen as Henry grabbed on to the cable with tender hands.

“HO!” responded the others, once again pulling with everything they had as they leaned back.

Henry held on tight, despite his burning palms. Up and down the line, the others did the same. And this time, it worked. Instead of his hands slipping painfully down the rope, he felt the rope begin to move. This time, when they fell to the deck, they took half a body length of cable with them. The gears of the windlass engaged and locked in their gains. Henry raised his estimation of the anchor-hauling device from “crude machine” to “technological marvel.”

“Again!” called Owen, his voice suddenly upbeat.

This time Henry sprang to his feet, and when he fell to the floor again, it was with a full body length of cable. There was no doubt anymore: The anchor was free from the bottom of the sea.

“Anchor aweigh, boys!” called Owen, and a few of the others cheered.

They resumed their three-count after that, hauling in cable hand over hand. In a mere five fathoms of water, and with the help of the gears of the windlass, it wasn’t long before the anchor was snug to the side of the boat. Henry’s muscles burned and his hands screamed, but he couldn’t help but smile. The anchor was up and he had actually helped. For the first time since he’d taken his initial unsteady footsteps aboard the Polaris, he felt like a part of the crew.

“Starboard now!” called Owen, and Henry’s smile vanished. He’d forgotten there was another one. He brushed his burning hands on the soft, worn-out cloth of his pants and prepared to do it all over again.

Aaron and Thacher spat into their hands and rubbed them together, and even that act seemed impressively coordinated to Henry. But the second anchor came up easier, and once again, Henry managed to do his part.

Without a moment’s rest, the order was given to set sail, and Henry immediately descended back into uselessness. With a sharp bark of “Lay aloft, you rascals,” the others swarmed up into the rigging. Manny and Owen led a breakneck race to the top of the forward mast. Henry was rooting for Manny but didn’t see who won, because he was attempting to climb the rigging himself. He put his hands on the shrouds and his feet on the lowest ratline. Then he stepped up onto the next ratline, waited for his foot to sink and settle into the rope, and moved his hands a bit farther up the shroud. He was glad he’d left his boots behind today—bare feet did make it easier. Still, he felt like he could climb all this rope quickly or safely, but not both.

Fifteen feet up, the boat pitched to the side on a gentle swell, and Henry hugged the shrouds and closed his eyes tight. When he opened them again and looked up, he saw the others already at the very top of the mast, spread out across the royal yard. The mast reminded the botanist’s assistant of the trunk of a tall, impossibly thin tree. That made the yardarms the even thinner branches—and that made the others climbing across them just plain crazy.

He took his first quick look down, and that was it for him. Even though he was less than a fraction of the way up the mast, the deck already looked far away and bone-crackingly hard. Henry looked up again as the others leaned their chests into the narrow wood of the yard, their feet hooked into the ropes below, and unwrapped the tightly furled sail. “Let fall!” called Owen, and the small, high royal sail cascaded down.

The others quickly descended to the topgallant sail and repeated the process. This time, he just watched them. I will need to know what to do when I get up there, he reasoned. He felt useless and guilty, though, and as they went to work on the topsail, Henry resumed his slow creep upward. He went rope by rope, with all the speed and vigor of a drowsy sloth. His problem wasn’t a lack of energy, though. His problem was that his heart was pounding like a bass drum in his chest and his hands had begun shaking badly. He inhaled deeply, desperately trying to calm his racing nerves. As he exhaled, he heard Owen bellow, “Let fall!”

Suddenly, the heavy rolls of the mainsail were released, nearly hitting Henry in the head. An avalanche of rustling canvas rushed past, and Henry found himself more or less engulfed by it. Before he could gather himself, he heard a thundering above him and saw the others descending at speeds that seemed halfway between climbing and falling. He hugged the shrouds again as the others jostled past him.

He heard their feet slap the deck one by one as he reversed course and began his careful climb back down. By the time he reached the deck, the others had ropes in their hands again and were hauling still other sails up. He rushed over to grab a rope but couldn’t find a spot.

“Joining us, are you?” said Thacher. “How kind of you.”

Henry’s face burned with embarrassment, but he was pretty sure it was hidden by his sunburn. Aaron shifted his grip and slipped to the other side of the rope to make space for him. Henry mouthed a silent “thank you!” and grabbed hold.

The Polaris had two masts, with a swinging menace the others were calling a “trysail” behind the second mast and an assortment of triangular “jibs” in front of the first. It amounted to a vexing assortment of sails. Some of them had to be dropped down, some of them had to be hauled up, and some of them seemed to require both. Baffled by both the words and actions, Henry just tried to find the end of as many ropes as possible and to heave when he was supposed to heave and ho when he was supposed to ho.

He made a dozen mistakes and was sure the others considered him useless. He just hoped Owen hadn’t seen the worst of his blunders. With the anchors up and the first sails already bellied out by a stiff morning breeze, Owen had retreated back to the ship’s wheel to steer them away from the island and the breaking waves on its not-so-distant shore.

Setting sail with a crew so small, in every sense, was long, hard work. Once it was over, Henry leaned against the railing, huffing and puffing. He looked down at his rubbed-raw hands and then up at the fruits of their labor. The wind wasn’t particularly strong—certainly nothing compared to the gale the night before—but with so many sails set, it did the trick. What seemed like acres of pale canvas were puffed out farther than a chipmunk’s cheeks in the fall. He could even hear the wind whistling through the rigging.

Henry leaned over the side and saw the bow slicing through the waves and leaving a white wake behind them. Manny wandered by and peered over the side too. “What are you looking at?” asked Manny.

“We’re moving nicely,” said Henry, pointing at the soft wh

ite spray that flew up as the ship sawed through the water.

“Oh,” said Manny. “I thought there might be a dolphin or something.”

They both scanned the water for a moment, as if looking for one. Then Manny looked up at the full sails. “But, yes, we are hauling wind now.”

Henry nodded. He liked that phrase: “hauling wind.”

Manny walked away, adding softly, “I just hope we’re not hauling too much of it.”

Henry looked back up at the sails. The wind whistled. The wood groaned.

An hour later, the burning sun was high overhead. The ship had originally dropped anchor for its fateful, fatal meeting shortly after crossing the equator, and they were still close to that imaginary line around the waist of the world. The sun here was bright and hot, and the days were long.

Henry and Aaron had just taken a grueling turn on the chain pump. This one didn’t pump seawater onto the ship but rather bilge water off it: out of its briny bottom, through little grooves in the deck, and over the side. It was bigger than the other pump and located in the waist of the ship, directly over the lowest point in the bilge. It worked with a sort of seesaw mechanism and would have been hard work with two men on each handle. With one boy per side, it was murder.

As they stepped away to let someone else have a go at the pump, Henry’s stomach rumbled beneath his sweat-stained shirt. He heard steps behind him but was too worn out to bother turning around to see who it was.

“You! Henry!”

The voice and volume told him it was Owen. He closed his eyes, sucked in a slow breath, and turned around. “Yes?”

“You were useless raising sail this morning,” said Owen.

Henry just looked at him. He couldn’t exactly deny it. Thanks for the kick in the britches, he thought.

“You know that, right?” prodded Owen.

Henry sighed. “I was hoping you wouldn’t notice,” he said, too tired to lie.

Out of the corner of his eye, he could see a few of the others turning to look his way. Owen broke into a wide smile. Whatever came out of his mouth next, Henry knew, would not be good.

“Now you can make it up to us!” he said.

Henry reached up and dragged the back of his hand across his sweaty forehead, an attempt to point out that he had just taken a long, hard turn on the pump. “Oh yes?” he said. “And how can I do that?”

The others had stopped working now and were staring at him openly. It occurred to him that he was quite possibly the only person on deck who didn’t know what was coming next. He was too tired and hungry to think straight. Hungry, he thought. Oh no …

Oh yes.

“You can head below and fetch up dinner for us,” said Owen.

“Below?” squeaked Henry. “Alone?”

He winced. He hadn’t meant to say that last part aloud.

Owen cocked his head to the side like a curious dog. “How much do you suppose we’ll eat? One person should be more than enough to haul it.”

Defeated, Henry allowed his eyes to drift back toward the half-swabbed grating and the darkness underneath. Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad now, with daylight leaking through. Maybe it was all in his head. The thought gave him a bit of courage. Be a scientist, he told himself. Be rational. “Where is it?” he said, straightening up a bit. “How much do I bring?”

“Do you really not know?” said Owen, seeming legitimately surprised.

“In the galley?” Henry ventured. He knew he should know this, and he didn’t want to get it wrong with everyone watching. “Or, wait, the pantry?”

Owen’s fake smile settled into an authentic smirk. “Useless,” he murmured.

Off to his left, Manny chuckled lightly—and at exactly the wrong time. Owen raised his left hand and pointed toward the sound. “You,” he said. “Spaniard. Go with him. Make sure he doesn’t bring us lamp oil for lunch.”

“Aah! But! Why? I-I-” Manny stammered.

Owen’s smile returned. “I suppose we could wait till this evening to eat …”

“No!” blurted Thacher and Mario at the same moment.

Manny turned and glared at Mario: Even you?

“Fine,” Manny said, and then spat disdainfully onto the deck.

I just swabbed that deck, thought Henry, falling in line behind Manny as they headed toward the aft hatch.

Manny turned and looked at him. “You are just useless,” said the Spaniard, the soft, swooping accent making the harsh words sound elegant and almost feminine.

“I’m not just useless,” protested Henry.

“Oh no? Then what else are you?”

“I’m useless,” clarified Henry, “and scared too.”

A quick smile flashed across Manny’s face as they reached the hatch and started down the ladder. “Then we have something in common.”

Henry took one last breath of clean salt air and then headed below. Work resumed on deck as the two descended into the deep shadows. There was a pool of sunlight at the base of the ladder, and when Henry reached the bottom, Manny stepped aside just enough to let Henry stand in it as well.

“That’s not good,” said Manny, pointing forward.

Henry blinked a few times as his eyes adjusted to the dim light beyond. The lantern they’d relied on the night before lay smashed on the floor, surrounded by a pool of oil.

“It must have fallen from its hook in one of the swells,” said Manny.

“That’s unlikely,” said Henry, considering it. The thing had stayed on its hook through the mountainous waves of the storm. Why would it fall during the modest swells that followed? But if it wasn’t the swells that knocked it down … “Oh,” he said.

Manny looked at him very seriously and then repeated the words slowly and clearly: “It must have fallen from its hook in one of the swells.”

This time Henry didn’t argue.

“We’ll have to replace it,” added Manny. “We can take the one from the galley.”

Henry peered into the shadowy distance in front of them. He swallowed loudly.

Manny stared straight ahead and took one tentative step out of the circle of light, then another.

Be a scientist, Henry urged himself, and followed.

Manny peered at the path ahead. The sailors called this the between deck, located as it was between the sunlit main deck above and the ship’s dark and cavernous hold below. It was between daylight and darkness, and the two mixed uneasily here. Moving slowly away from the stern of the ship, Manny and Henry entered a dark space in between the hatch and the first grating.

Should they speed up to get through the darkness faster, wondered Manny, or slow down, move carefully, and listen? The sound of Henry stumbling clumsily in the dark provided the answer. Slow, it was.

Manny took slow, shallow breaths and felt the weight of the world closing in, with a chest that felt constricted beneath two layers of shirts and a head that pounded beneath the tight black cloth wrapped around it. The Spanish style … Ha! No Spaniard with any sense would wear extra layers on the equator!

Eyes wide open, ears alert, they crept forward. They reached the grating, its light hitting the floor in a checkerboard pattern. Manny exhaled. They reached the crew berth, and its cluttered expanse was all that stood between them and the galley. At least, they hoped that was the only thing standing in their way.

They stepped carefully over dead men’s boots and sea trunks. The smell of sweat and chewing tobacco still hung heavily in the air, but it was better than the ghostly, unnatural sweetness. They reached the galley. The door hung half open, a faint light radiating from inside. Manny’s heart pounded. Henry gulped down foul air.

“Come on, let’s get this over with,” Manny growled, slapping the door with an open palm.

The door swung open and smacked the wall. A moment later, as if in response, a second thump sounded from somewhere in the darkness. Manny whirled around but saw only Henry’s face, his mouth formed into a big round O and his eyes almost as wide.

�

�What was that?” Henry said, pointing farther down the passage. “It came from somewhere up there.”

Manny grabbed him by the shirt, pulled him inside the galley, and then slammed the thin wooden door behind them. But their troubles would not be shut out so easily.

The door slammed: PAK!

It was followed immediately by another sound from out in the passage: BRONK!

Was that closer, thought Manny, or just louder?

Henry stammered out a series of half thoughts: “But … what … is there someone … no, but …”

“Let’s just get the food,” said Manny, drawing some thin comfort from the closed door and the light streaming in from above them. The galley had its own small grating, more for venting the cooking smoke than for letting light in, but it served both purposes.

“Take that down,” said Manny, pointing to a grimy old lantern hanging from a hook on the wall.

As Henry reached up for it, Manny bent to tip a barrel of salt pork. If it wasn’t too full, they could take the whole—“EEEEEEEEEE!” screamed Manny, high-pitched and loud, as a dark shape bolted out from behind the barrel.

Henry gasped and fell back, juggling the lantern in both hands as if it had suddenly come alive.

There was a scrabble of claws on wood, digging in, gaining traction, and then the quick thump of small footsteps.

“Daffy!” cried Manny.

Henry finally gained control of the elusive lantern. He let out a long breath and said, “You’re kidding me.”

Daffodil, the ship’s cat, reached the door. Finding it closed, she spun around to face the intruders. Her eyes glowed faintly in the shadows. As soon as she identified the newcomers, she settled onto her haunches and began to clean herself, unconcerned.

“Bad cat!” huffed Manny. “¡Gato malo!”

Another strange sound filled the little galley, and it took Manny a while to realize that it was Henry, laughing softly.

“What’s so funny?”

“You,” he said, adding a quick imitation of Manny’s scream: “EEEEEE!”

He kept the volume down but got the pitch right. Manny burned with embarrassment.

On Thin Ice

On Thin Ice Plunked

Plunked The Final Kingdom

The Final Kingdom Valley of Kings

Valley of Kings Surrounded by Sharks

Surrounded by Sharks The Stone Warriors

The Stone Warriors Gentlemen

Gentlemen Book of the Dead

Book of the Dead Polaris

Polaris Amulet Keepers

Amulet Keepers