- Home

- Michael Northrop

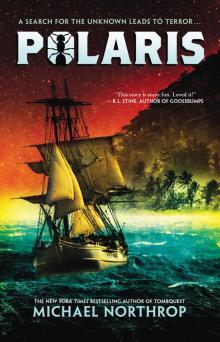

Polaris Page 3

Polaris Read online

Page 3

He felt the ocean spray against his cheek and tasted its salt on his lips. Slowly—very slowly—he began inching his way along the rail toward the cabin. Though he was no sailor, Henry was skilled at observing natural phenomena. Even in the dark, he quickly realized that the rolling swells arrived at more or less regular intervals. He timed his movements accordingly, clinging tight when the waves lifted him high in the air and moving forward quickly as the ship briefly leveled off. And it was in one of those precious moments—when gravity was restored and the deck was less perilous—that he dashed across the quarterdeck for the cabin door.

He grabbed the handle as the boat began to pitch deeply, but he remembered too late that the door had been knocked from its hinges. It was held in place only by its iron lock. As the ship rose higher and higher on its side, Henry clung tightly to the door handle. Under his weight, he felt the soggy wood around that lock begin to splinter and crack.

Oh no, oh no, oh no!

Letting go meant flying straight into the waves. Holding on meant doing the same a few seconds later—with a door on top of him.

Suddenly, an arm appeared in the dim gap between the broken hinges. Its strong hand grabbed on tight to Henry’s shoulder. Once the boat settled and began to roll back, the hand tugged him toward the gap. As the boat passed through level, Henry turned sideways and scrambled inside.

And there, in the lamplight, he saw the face of the last person he’d expected. Henry mumbled a quick “thank you,” but Owen ignored him. The strong-armed cabin boy was already at work lifting the door back onto one broken hinge and sliding some slim piece of metal—a fork, perhaps—through to keep it there.

Henry clutched the other side of the doorframe as the boat began to roll again. The hanging lamp stretched the shadows as it swung. He saw five other sodden boys. Including himself, their ages couldn’t total more than eighty years. And yet, as the thunder roared overhead, he realized that this was it. All that was left. They were utterly on their own.

“Will we survive this storm?” he said as the thunder faded.

For a few moments, no one answered. The only sounds were the wind and sea outside and the teacups tinkling in their snug cupboard.

“Better men than us have already died tonight,” said Owen. His words were angry, but his voice was sad. “But yes, we’re anchored firmly in five fathoms, and the island will take the worst of the wind. It will be a dirty night, and we’ll have plenty of pumping to do, but we’ll make it.”

Henry nodded, still clutching the doorframe tightly as Owen moved easily across the rolling floor of the little cabin in a bent-kneed crouch. Henry looked down at the bare feet of the others and then at his own soggy boots. Owen wheeled around to look at him. “But you have a lot to learn,” he said, “if you hope to last another day.”

They rode out the storm in the captain’s cabin. Most of the crew had been at sea for long enough that seasickness was a distant though unpleasant memory, but not everyone was so lucky. Henry threw up into a chamber pot and then stared balefully down at what he’d done. His seasickness actually seemed to get worse as the rolling swells began to subside. Manny recalled those miserable days, when a gentle rocking could be as bad as a raucous rolling.

Soon the wind began to die down too, the steady howling reduced to an occasional loud gust. Manny watched the swinging lamp and saw the storm fade in the settling of its shadows.

“Just a squall after all,” said Aaron.

“No,” said Owen softly. “The seas were too high. It was a storm, all right. We caught the tail end of it.” His voice sounded distracted and distant, so different from its usual bluster that Manny turned around to look at him. He was sitting in the captain’s chair, contemplating a teacup. That was the captain’s too, Manny figured. Owen was visibly devastated, like a puppy that had lost its master. An arrogant know-it-all puppy, but still.

One by one, the survivors rose to their feet, except for Owen. The captain’s cabin, while a little low for actual adults, was the perfect height for ship’s boys. And whether they’d ridden out a storm or a squall inside, it had lasted only a few hours. Now it was time to see to the ship and salvage what sleep they could from the remainder of the night.

Manny knew one thing for sure: They’d all need their rest. The next day would dawn on a boat without captain, carpenter, gunner, or doctor. Every crew member rated able seaman had been lost to the sea—by choice, by blade, or by bullet. Names and faces flashed through Manny’s mind. Maybe not friends, exactly—they were too unequal for that—but some of them had been kind and generous. If there was one silver lining to all that rain, Manny thought with a shudder, it was that there’d be none of their blood left on the deck.

“I suppose we should head below deck to sleep, then,” said Aaron tentatively.

Manny shuddered again. The cramped confines below deck were dark and dank on any sailing ship, but lately on the Polaris they had become something even worse. And Manny wasn’t the only one to feel it. No one moved for a few long moments. Finally, Thacher broke the silence.

“Should we?” he said, his voice little more than a whisper.

Manny was shocked. It was a crazy thing to say. The crew always slept below deck—on this ship, on every ship. And yet … After what had happened on this vessel just hours earlier, and with only the six of them left aboard, could anything else on the Polaris truly be called crazy?

Reflexively, a few heads looked back at Owen, but he seemed unaware of the exchange. He was lost in thought, still sitting there contemplating his teacup. Has he found a crack? wondered Manny. Or has he cracked himself? And if so, is he the only one? There’d been sniffles from some of the others as the storm died down, and a few little sobs they’d tried to time with the fading thunder. With raw survival no longer at stake, Manny knew, the dire situation was starting to hit home.

With no one challenging him, Thacher continued, his voice a little louder. “Should we head below? Now, after all that has happened? Now, on this pitch-black night? Now, when we would be all alone down there?”

The questions hung in the air like stars.

“I don’t want to,” admitted Aaron.

“I hate it down there,” added Henry. Manny looked at him. He was such a strange boy. He seemed to live in his head and had barely been seen or heard since the loss of his own master.

“I do too.” This time the voice came from right beside Manny. It was Mario. Manny flashed a quick warning look. Don’t forget, it said. There was no need for more. Mario knew the reason well: The darkness below might hide dangers, but it hid secrets too.

Mario shrugged and added, “There is something bad down there. And now, with no men left …”

With Owen still locked in silence, all eyes turned to Manny, who let out a long sigh and then an admission. “There is something bad down there. Something … wrong.”

“Something,” said Thacher, “or someone.”

Aaron gasped, and Manny barely managed to avoid doing the same. Once again, Thacher had dared to speak the unspeakable. And in doing so, he had broken down a dam. The stories began to flow forth. And they weren’t normal stories.

They were ghost stories.

“I’ve seen things,” whispered Aaron.

The room went silent. Manny stared back at Aaron. Even Owen glanced up from his cup.

“What have you seen?” coaxed Thacher, the pale scar above his left eyebrow glowing softly in the lamplight, giving him an expression both curious and strange.

“Well …” Aaron began. Manny leaned in a little closer. “It’s shadows, mostly. It’s hard to say; it’s always so dark down there.”

Manny pictured the world below deck. There were no windows at all. During the day, light filtered in through any open grates or hatches on deck. But at night or in foul weather, there was barely any light. A lamp hanging fore and aft and maybe a trickle of moonlight, at most. There might be other lamps burning in the officers’ berths or the carpenter’s cabin, but prec

ious little good that did the crew.

Aaron went on. “So when I say shadows, it could be just a shadow of a shadow under a full moon, but the thing is—”

Thacher cut in: “The shadow doesn’t look right.” Everyone turned to look at him. “It doesn’t move right.”

“Yes!” Aaron agreed. “That’s it exactly. It looks human enough, when the light catches it. But the way it moves—shuffles along. At first, well, I thought it was poor old Wrickitts, but then he took to his sickbed.”

This time it was Mario cutting in: “And the shadow haunted us all the more.” Manny shot another warning look over, but Mario ignored it. “I saw it too. Always late at night, always out of the clew of my eye, along the wall, at the door, never out in the open.”

“And then there’s the sound,” added Aaron. “A horrible sound, a—a—” He searched for the word and then found it. “A dragging.”

“A dry, raw scraping,” added Thacher.

Manny eyed him carefully. Thacher was throwing fuel on the fire. What was he up to? The story below deck was that Thacher had come from a respected Boston family that had been ruined—a rich family turned poor. His fine education was cut short, and being the youngest of the brothers, he was sold into servitude to help pay off the family’s debts. Is it true? Manny wondered. Thacher definitely talked the part—but he didn’t get those scars at a piano lesson.

“Shadows, sounds,” said Owen, finally putting down his cup and looking up. “That could have been anything. The ship is full of sights and sounds at night. A crew mate on the way back from the head, rats in the scuppers …”

Owen’s words trailed off. He looked small sitting in the big chair. Thacher looked down at him and a slow smile spread across his face. His other scar, the one on his cheek, folded over on itself like a white worm writhing. “Aye, no doubt, so many sights and sounds. But then, of course, there is the smell …”

Owen looked away, and that’s when Manny knew he’d seen something too—seen it and heard it and smelled it. Thacher went on, choosing his words with care: “A smell like rotting flowers, at their sweetest just before they turn brown and fall away …”

“That was the worst part,” said Aaron. “The shadow would shuffle across some dark corner, scraping its way by like fingernails on stone, and then, when you were lying there, telling yourself it was just your imagination—”

“Or a dream,” added Mario.

Aaron nodded. “Just then, you’d smell it.”

“The dense funk of the crew and all their earthly odors turned into a field of dying flowers,” said Thacher.

The cabin was silent for a moment.

“Not like a flower,” said Henry. It had been so long since he’d spoken that Manny had almost forgotten he was there. But all eyes were on him now. He shifted uncomfortably at the attention.

“What did you say?” said Thacher, a hint of warning in his voice.

“It’s just that I am a botanist’s assistant—well, I was—and I have smelled something like that before. It’s sweet, as you say, but more like a fungus. Well, certain funguses …”

He descended into mumbling: “Sickly sweet, to be sure … but a certain yeastiness to it … quite unmistakable once—”

Thacher abruptly cut him off. “I’ll tell you what it is,” he spat.

Don’t say it, don’t say it, don’t say it, thought Manny.

“It’s Obed Macy!”

Manny’s blood went cold. He’d said it.

“Thing is, Obed liked flowers,” said Thacher. “At least, before he took that chest down into the hold and disappeared for good.”

“What do you mean?” said Aaron.

“I was with him when he came back from shore once. I’d spent my money on sweets, but all he got for his was a sad bunch of cut flowers. ‘What are those for?’ I asked him, and do you know what he said?”

Thacher looked around the room.

“What?” breathed Mario.

“‘Fer me pillow,’” said Thacher, imitating Obed’s voice and accent perfectly. “‘So me dark little world don’t smell so bad.’”

More silence.

“That’s right!” crowed Thacher. “It’s a hard life being a hold rat. You think the smells are bad where you lay your heads, try working in the hold, walking over all that stinking sloshing bilge water. You’re more liable to step upon a drowned rat than dry wood.”

Thacher glared around the room, daring anyone to challenge his claims. “I’m the hold rat now, but I’ll tell you something funny—something most peculiar …”

He paused, and Manny knew for certain that what he would say next would not be funny at all. “I’ve been all through that hold looking for his body. Haven’t found a thing … but it smells awfully sweet down there these days.”

“It’s him …” said Aaron. “Obed Macy.”

Thacher nodded solemnly, but then another thought occurred to Aaron. “Or it could be old Wrickitts and his perfume.”

Thacher cocked his head, considering this new possibility. Manny groaned softly.

It was all over. Two potential ghosts were simply too many for the young crew. By a vote of five to two the decision was made: The survivors would sleep above deck until they reached port or sank the ship trying.

“Of course you two are welcome to sleep down there,” Thacher said to the no voters, Owen and Manny.

Owen let out a dismissive snort and said, “Like I’d trust you urchins alone in the captain’s cabin. The silver in here belongs to my family, you know.”

Whether Owen meant it or not, Thacher flinched when he heard those words. So his family had sold him off, after all, thought Manny, along with the silverware, no doubt.

Manny shot Mario another look. It was less of a warning this time—Mario’s yes vote had already been cast—and more of a plea: I hope you know what you’re doing. Sharing this little cabin might feel safer, and even cozy, to the others, but it was a little too close for comfort for them.

Reluctantly, Owen unhinged the broken door and the young crew shuffled out into the night. The rain had stopped, and the dark clouds had begun to pull apart. A hint of moonlight shined down on the deck as the ship rocked gently to and fro. Owen and Aaron removed first the long wooden battens and then the thick tarpaulin cover from the aft hatch with sure, practiced hands. As they waited to head below and retrieve their meager possessions, the others took deep breaths of fresh salt air. All of them hoped it would be the sweetest thing they’d smell that night.

This is a mistake, thought Owen.

Even worse, it was a mistake that he’d allowed the others to force on him. But then, it always seemed to be that way. Had he ever been wrong about such a thing on his own? About anything, really? He considered it. No, he decided. Not me.

He stepped aside and let the others head down the hatch. This hadn’t been his idea, so why should he go first? The ladder was sturdy and angled—almost like stairs, really—and he chastised himself as he headed down. He’d been lost in his own head back in the cabin—moping over his uncle, turning over that stupid cup—and now it was too late. It just wasn’t proper for anyone to sleep above deck. He corrected himself: anyone but the captain. The captain … He’d been his mentor, his kin, and every once in a while, maybe even his friend. But now he was gone.

Owen felt himself slipping back into something far darker and deeper than the shadowy space below deck, but he shook it off. He couldn’t afford any more self-pity. He descended the ladder, last in line. As he sank below the hatch, even the faint light of half a moon vanished. He was halfway down before Mario found the aft lamp and lit it.

Owen reached the bottom. Water had slipped in through the hatches and grates, and he felt the slick wet wood under his feet. The Polaris was a sturdy ship, but she’d never been the tightest or the driest.

The heavy old lamp seemed to create more shadows than light, and Owen eyed the edges of that light, where the shadows gave way to pure black in the corners and farther

on. And then, despite himself, he pulled a deep whiff of air into his nostrils.

The smell that greeted him was a dank mix, with hints of human sweat and the mold growing in the dark. It wasn’t what anyone would call pleasant, but it was as it should be down here. Owen let the breath out through his lips.

“Let’s take the lamp with us,” said Aaron.

Owen felt like he should object, assert himself. He’d been outnumbered on the original decision, brushed aside due to his distraction. But now he’d recovered, and taking the lamp was another breach of protocol. Owen opened his mouth, but nothing came out. He looked up at the grates. On a clear night, with the moon and stars above, they let in almost enough light for a dark-adapted eye to see by. But the grates were still covered for the storm and pitch-black.

“Yes, let’s take it,” said Mario, and the next thing Owen knew, Aaron had taken it down.

Owen remained silent. Outvoted again, he told himself. But there was something else going on, something apart from weak light and deep shadows and what he did or did not smell. He was standing just below the aft hatch and facing forward. He still hadn’t taken a look behind him. Because that was where the officers’ berths were.

And the officers were all dead, or worse: traitors. He remembered the sight of the launch heading out into the rising seas. Dead and traitors.

And suddenly the light was on the move, heading away from him. Owen hustled to catch up. The group stayed tightly packed as they passed by bulkheads and beams. With too many bodies in between him and the lamp, Owen could barely see a thing, but he knew from memory that they were passing the breadroom.

“Should we?” ventured Mario.

“No!” Owen barked. There’d be no midnight snacks while he was around. What was this, anarchy? It felt good to assert himself, at last. He shouldered his way closer to the front of the group as they arrived at the crew’s berth.

He looked around at a museum of the dead. Battered trunks against the walls, coats and hats hanging from pegs, foul-weather boots flopping over on themselves … Everywhere he looked, he saw the scattered possessions of dead sailors. He’d seen such ownerless debris before: when the expedition had returned, cut in half. But all signs of those lost men had been pushed aside by the remaining sailors, quickly snatched up or displaced by the hustle and bustle of a working ship. This time, there’d be no recovering. The wounds were too deep. Owen felt a shiver rise from his core. “Gather your things, boys,” he called. “And make it quick.”

On Thin Ice

On Thin Ice Plunked

Plunked The Final Kingdom

The Final Kingdom Valley of Kings

Valley of Kings Surrounded by Sharks

Surrounded by Sharks The Stone Warriors

The Stone Warriors Gentlemen

Gentlemen Book of the Dead

Book of the Dead Polaris

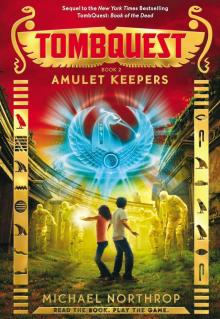

Polaris Amulet Keepers

Amulet Keepers